It was just another night. Not too out of the ordinary. My patients were all tucked in, chart checks were done, I had even had time to go off the floor for a half hour to eat while watching Sportscenter.

Out of my 4 patients, only 2 were on telemetry therefore, only 2 required the 4am vitals. That I figured, could wait until 4:30, maybe even 5am. Heck, why not let them sleep a bit? One had come in at the god-awful time of 0-dark-thirty the previous night and had unfortunately kept the other up most of the night in the ever time-consuming process of admission paperwork (even though I am a bit of a whiz at it…).

I had been keeping my eyes and ears open, slowly watching the little green squiggles of the EKG lines trace their way across the monitor, trying valiantly to stay in some semblance of wakefulness. One of them, Mrs. S., I had been keeping a closer eye on than usual. Nice older lady, in with pneumonia, A-Fib with RVR and ground level fall. The pneumonia had been getting better, instead of crackles and wheezes all the way into her upper lung fields, they had retreated down to the bases, still there but not as bad as they had been. Her A-Fib had been wrestled under control with a little help for our friends Cardizem and metoprolol, ususally she lived in the 90-110 range, give or take, even lower when she slept. All night, she kept coughing, that pneumonia cough, it never really brings anything up, but never really goes away. Just nagging enough to keep her partially awake.

But tonight it was her rate that was on my mind. All night it had been creeping up, never drastically, but like the cough, just enough to keep my attention. It was 3:30 and she was hanging out in the 140s now and had been for awhile, so I was starting to get ready for some meds. She had just rung the bell and our oh-so enthusiastic aide went to see what she needed, (mind you, it was that kind of a night for everyone).

As she comes out she says, “Hey Wanderer, she says she’s feeling a little short of breath, not too good at all.”

“I’m on it,” was my reply. As I’m heading into the room the “oh- shit!” alarm on the monitor starts going nuts. “Hey Wanderer,” someone shouts from the station, “That’s your lady, she went up to like 180 and is sustaining in the 160’s!”

“Shit.” I mutter to myself as I bust into the room like Patton himself. She looks up at me with that worried scared face and says after she stopped coughing, “Y’know, my cough is getting worse and I don’t really feel like I’m getting a good breath. And my heart feels like it’s beating really fast.” I can hear her lungs from the foot of the bed, they sounded like Sponge Bob could live inside the ocean that was filling her pulmonary system.

Cool as a cucumber, but starting to shake just a little, I said, “Well let’s check this out,” and start hooking her up to the in-room monitor. The monitor starts bing-ing the “oh shit!” alarm again: rate in the 160’s. I reach down feel her radial pulse, yep, feels about right. I take a listen with my stethoscope. Yep, wet, wet, wet breath sounds all the way up, from the bases to the tops. And her cough had turned from non-productive to a more milky, frothy kind of gunk. “Not good Wanderer,” I said in my head, “I need to get the rate down.” So I sit her up in bed, turn the 02 up a little more and have her take some nice slow breaths and tell her, “I’m going to go grab some medicine to slow your heart a little OK?” Hoping that the adrenaline now pumping full-bore doesn’t make my voice quaver at all. She nods. “I’ll be back in a moment, call me if it gets worse.”

Out to the nurses station, I grabbed the phone to page the intern. With the page on the way I went into the med room to grab the metoprolol I had intended to grab before the aide grabbed me. Pull the med out of the Pyxis, override for Lasix and my pager goes off. “413” code for phone call. Pop out of he room, “It’s Dr. Night-Intern on A” someone says. I pick it up, “Dr. Night-Intern, Sir? You guys are still following Mrs. S, right? came in with pneumonia and A-fib with RVR?”

“Ahh…” I hear pages rustling oint he background, “Oh,yeah,we still are…”

I cut him off, “I think she’s trying to flash over on me, she has frothy sputum, lungs sound wetter than they did at start of shift and her rate’s been sustaining above 160 and has gone as high as at least 180. I have metoprolol PRN, but can I get an order for some Lasix to help get the fluid off?”

“Ummm, uhhh,” I’m watching the monitor, rate is 170 now, “Well, what’s her renal function like?” he comes back with.

“BUN and Creat are WNL, K this AM was 4.3, she got 40 mg of IV Lasix this morning.” hoping he hears the urgency in my voice. I really don’t want to have to call a rapid response now.

“OK, did the Lasix work this morning?” I smack my hand against my head, time is not on my side right now I’m thinking, “Uh yeah, sounds like it worked great, she put out approximately 1500ml for day shift today.”

“OK, go ahead and give 40mg IV times 1, now…” he says.

I cut him off, “OK, what’s your P#?”

“Oh, does she have labs this morning?” he asks.

“Nope, no labs, want one?”

“Yeah, grab a comp and a mag this AM.” he comes back with, “P# is 1234567”

“OK, thanks Dr. Night Intern, I’ll call ya’ if you I need anything else.”

I look, it has taken all of 2 minutes, tops, but felt like a near eternity. I had already pulled the Lasix up after he had said “OK” (and who said we shouldn’t multi-task?). I looked up at the monitor as I headed back towards the room, looked like 160’s still, bumping to 170.

“OK Mrs. S, I have some medication here for you, gonna’ put it through your IV , OK?” She nods as we go through the JCAHO rigamarole of identification – name, DOB, cat’s name, mother’s maiden name and shoe size in Europena sizing – to determine that it really is Mrs. S. I grab a quick BP as I start to give the metoprolol. When the machine stops cycling it shows 140’s over 100’s. “Well, that ain’t good” I think to myself. I’m a little calmer now, but still riding the crest of the adrenaline surge. I finish pushing the metoprolol, as the machine cycles again, now we’re down to 140’s over 80’s, not great but better. Heart rate is already starting to drop, now sustaining in the 140’s. I push the Lasix and say, “I apologize to do this to you at this time of the morning, but it will help get some of that fluid off your lungs.”

She says, “It’s OK, it’s what needed to be done.”

I look at the rate, now we’re into the 120’s, respirations are down to about 18-20 and BP is running near her baseline of 120’s over 60’s. She even looks better already, that worried face is gone, in it’s place relief. “I’m just going to hang out here for a couple of minutes OK? Just to make sure we’re doing better.”

She looks up and says, “It’s OK, I’m already feeling better now. I feel like I can breathe a little better. I’m glad you were here to help me.”

“I’m glad I was too.” As I said that, I was thinking to myself that if I was as good of a nurse as you think I am, you wouldn’t have been in this situation. It’s really my fault that this happened at all, I wish I had the balls to say.

At midnight she had PO metoprolol due, but with holding parameters, HR <60, SBP <90. Being the ever-prudent nurse I am, I checked both prior to giving the meds. HR had been 110’s, but SBP was 88, so in concurrence with the parameters, I held it. Now, I know that there is no way to prove that was the precipitating event, but I felt deep down that maybe it had something to do with it. I talked it over with my colleagues and they agreed: it was a crap shoot. The pevious night her SBP had been fine but the dose dropped her 10 points and she had felt a little goofy and wobbly when she was standing, so I didn’t want to repeat that, but I wavered knowing that the primary reason for giving her the med was rate-control. In the end I didn’t give it. That’s why I kept my eye on the monitor all night long. That’s why I was coiled and primed, ready to run in, because I had that feeling in my gut that something might be afoot. It was a heck of way to re-learn a lesson, or at least give me bigger pause the next time to reconsider the meds I am giving. It taught me a lot about nursing judgment. We’re entrusted to make decisions that have life-changing effects on our patients and even when we think we’re making the right choice, we’re not always. I know that judgment gets better with experience but sometimes you get burned. The good thing though, was that it was caught early and treated before it got worse. Besides that, I realized that if this had happened less than 6 months ago, I would have called rapid response. Granted, I would not have been wrong to do so now, but I felt comfortable in not calling the team and managing it myself, knowing I had backup a mere phone call away.

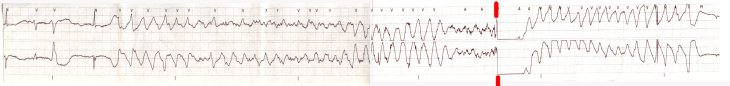

As I finished charting the episode and my adrenaline started to fade, the monitor tech came back to post the strips and asked, “Did you see how high your lady’s rate went?”

“No, I hadn’t. How fast?”

“It topped out at 201 and spent a lot of time in the 180’s. Is she OK now?”

“Holy crap, any wonder why she didn’t feel that great! She’s doin’ OK now. Nothing a little metoprolol and Lasix couldn’t fix!” I said with a grin and went on my way.

And the night continued. Just like any other night on the floor.